💓 Why Pulse Diagnosis is so difficult...

When I was a clinic supervisor, I would usually start by asking students what skills they wanted to work on. The number one answer was always, “Pulse diagnosis!”

And even though students spent time in the classroom learning the different definitions of the pulses, often when they got to the clinic they would just say, “I don’t even know what I’m supposed to be feeling for.”

And I felt the same way.

When I was a student I would often hear interns and teachers coming up with these elaborate, poetic descriptions of the pulse. It sounded like a wine-taster describing the subtle notes of a wine. And I was like, “Are you really feeling all those things, or are you just making that all up?”

So I decided to make a beginners’ pulse diagnosis course with a methodical, un-poetic approach to taking the pulse.

But first, I thought it might be helpful to talk about why pulse diagnosis is so difficult to learn to in the first place...

Why Learning Pulse Is So Difficult:

1. So many different translations!

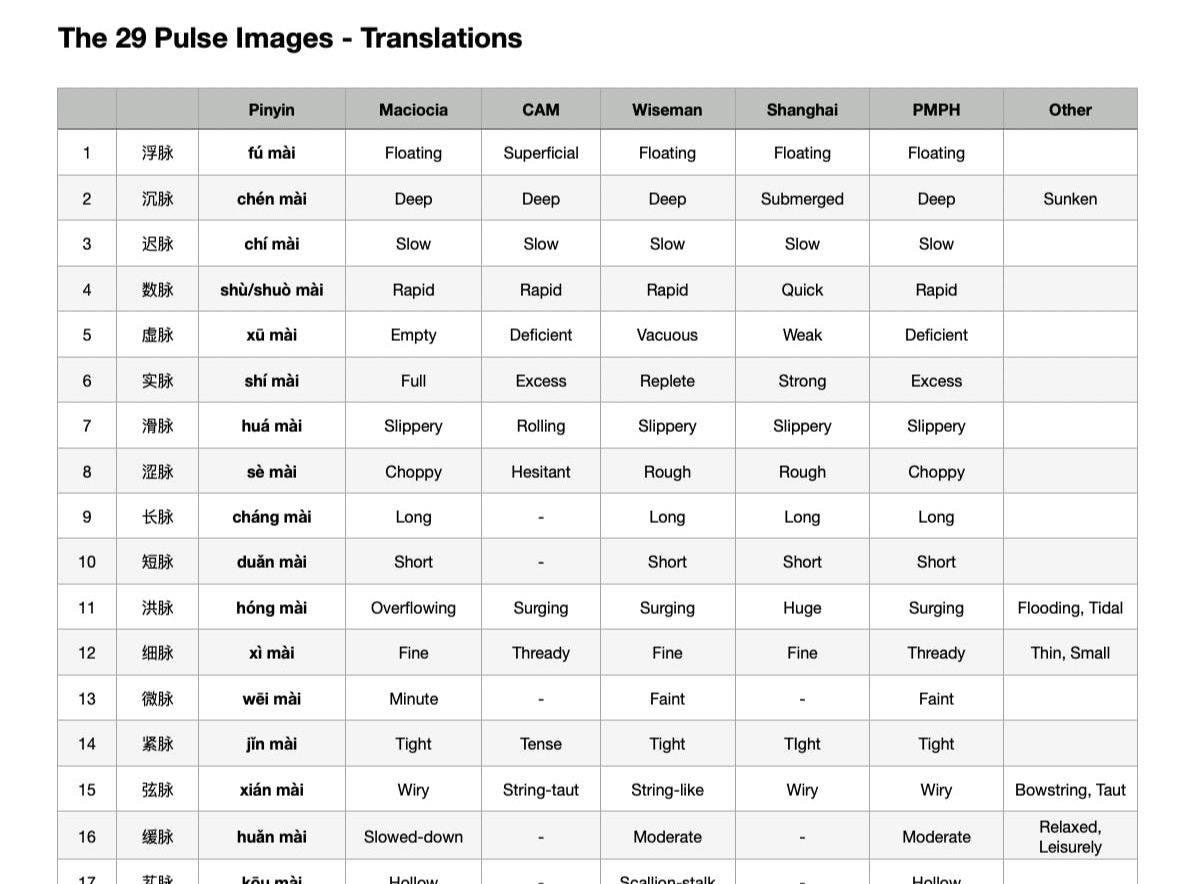

If you’ve been studying TCM for a while, you may be used to the fact that each textbook translates certain Chinese terms differently. The Ren Mai can be the Conception Vessel, Controlling Vessel, or Directing Vessel depending on which book you’re reading.

But this is especially problematic when it comes to the 28 pulse images. Each book (and each practitioner) likes to use different terms. And because many of the terms sound so similar, it can be difficult to know if it’s just a different translation or a separate pulse image all together.

For example, I’ve found that many people don’t realize the the thin pulse, the fine pulse, and the thready pulse are all the same pulse. They’re just different translations of xì mài (细脉).

Rough, choppy, and hesitant are all translation of sè mài (涩脉).

A deep pulse, submerged pulse, and sunken pulse are all the same thing.

To make things more confusing, sometimes one book will use multiple translations in the same chapter. For example, if you’re studying formulas, Bensky says that Wen Jing Tang has a “fine and rough pulse,” while Sheng Hua Tang presents with a “thin, submerged, and choppy pulse.”

So no wonder people are confused about thin vs. fine and rough vs. choppy. The authors of the book can’t even be consistent in a single category!

2. Unclear descriptions of pulse images:

Besides the many translations of the pulse image names, we also run into the problem of clearly describing what the pulse feels like.

Many classic texts use very poetic language to describe the pulse images (which is fun). But unfortunately, many teachers just present these descriptions “as-is” and don’t elaborate on what they actually mean.

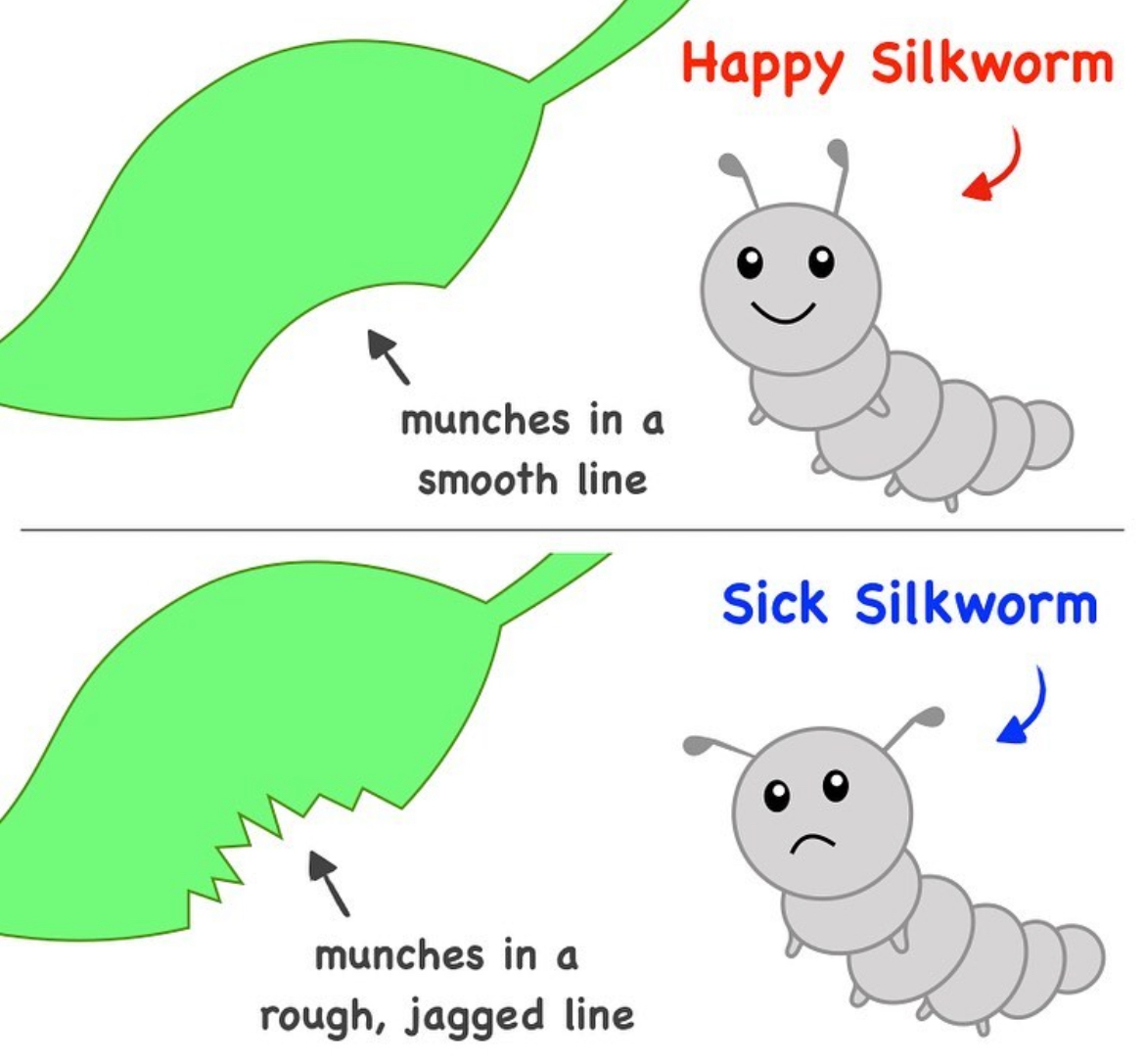

For example, sè mài (涩脉) — the rough, choppy, or hesitant pulse — is described by Li Shi-Zhen as a “sick silkworm eating leaves.” That’s a funny image, but not necessarily helpful in the clinic.

Here’s a more straightforward description: slippery and rough are two opposites. They each refer to how smoothly the blood is flowing through the vessel. So if the blood is flowing smoothly (like a nice sine wave), then the pulse is slippery. If the blood is not flowing smoothly (like an erratic or jagged sawtooth wave), then the pulse is choppy.

So these terms do not refer to the depth of the pulse, the strength of the pulse, the width of the vessel, or whether the vessel has a hard edge or not. These terms refer to how smoothly the blood is flowing.

It turns out when silkworms are healthy, they move smoothly and eat leaves in a smooth curve. But when silkworms are sick, they move erratically (speed up and slow down), and they eat their leaves in a jagged pattern. That’s what Li Shi-Zhen was talking about.

Or, this is an embarrassing one: for the first two years of clinic I could not figure out what a thin pulse was supposed to feel like. I thought that “thin” was referring to the viscosity of the blood. You know, like when you have paint and you want to make in thinner in consistency, you add paint-thinner. Or if a person is on blood-thinners then their blood will be thin. So I was trying to feel for the consistency of the blood.

Two years later a read a book that said thin, fine, or thread-like refers to the diameter of the vessel. So if the vessel feels narrow in diameter, that is a thin pulse. Conversely, if the vessel feels wide or large in diameter, that is a large pulse. Nobody ever told me that.

3. Lack of confirmation:

One of the thing that students have told me is that pulse is difficult to figure out because they don’t have experienced practitioners around to confirm that what they’re feeling is correct.

And this is one of the inherent difficulties with the pulse. With tongue diagnosis, everyone can look at the tongue at the same time and point to the cracks or agree on the color. This just isn’t possible with the pulse.

But, in my opinion, it isn’t absolutely necessary to get confirmation each time you take a pulse. If you approach the pulse in a systematic way, and if you know the proper definitions of the pulse images, you can do a lot with self study.

For example, I once asked a student to report on the pulse, and she said, “It feels deep and soggy.” And I immediately said, “No it doesn’t.” She was a little insulted: how could I tell her that she was wrong when I hadn’t even felt the pulse myself?

Well, the reason I told her she was wrong is because the soggy pulse (rú/ruǎn mài 濡脉) is by definition floating, fine, and forceless. So if the pulse isn’t floating (superficial), then it’s not a soggy pulse.

So suppose you first examine the depth of the pulse and find that it is floating. Then you feel for the strength of the pulse and determine that it is relatively forceless (it doesn’t have a lot of strength). Then you feel for the width of the vessel and find that it is thin. Congratulations, you have felt a soggy pulse!

So I think it’s better to learn a systematic approach to the pulse and know the correct definitions of the pulse images. That way you won’t always have to rely on confirmation from another practitioner.

Get More Updates and Download the Handout:

If you want to get more updates about the pulse diagnosis course, click the button below. I’ll send you articles like this one as I create each module and lesson. We’ll talk about things like how to properly place the fingers, straightforward ways to examine the pulse, the different positions, and so on.

Also, when you click the button, you’ll be directed to the handout above where I outlined all the translations for the 28 pulse images:

👉 Get Updates + Download Handout